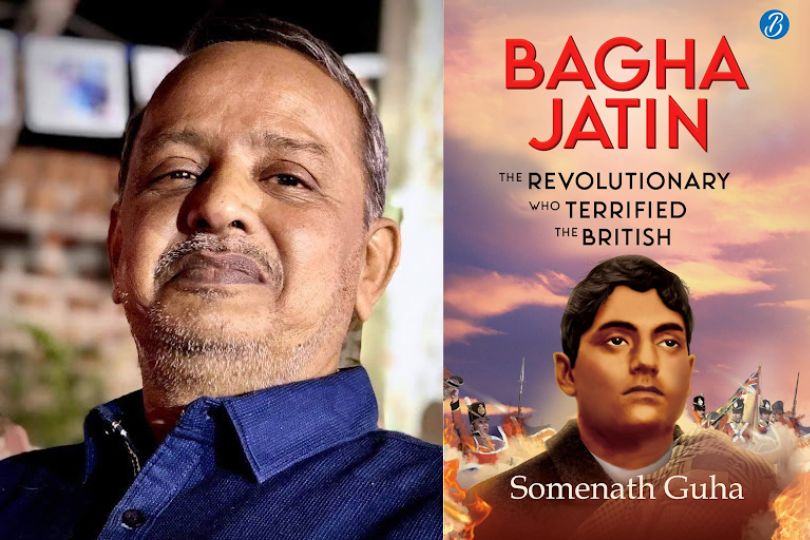

Interview with Somenath Guha, Author of "Bagha Jatin"

An insightful interview with Somenath Guha discussing his journey as a writer, his historical research, and the significance of retelling India's rich freedom struggle.on Aug 15, 2024

Somenath Guha has been writing prolifically in both English and Bengali since the 1980s. He freelanced extensively for various newspapers and periodicals. His first book in English, Garuda and Winged Horses: A Journey through Sikkim , was published in 2002. Thereafter he has mainly contributed to various Bengali magazines, news portals and blogs.

He has translated works of Russian poets and short-story writers into Bengali. He has also authored booklets on contemporary issues.

He is a former banker and resides in Kolkata.

Frontlist: How did you transition to becoming a full-time writer? Were there any specific challenges you faced during this transition?

Somenath: As I was a Banker, I could only become a full-time writer after I retired in 2018. Before that, I wrote in the evening after returning from my job and mostly on Sundays and holidays; in that sense, I wasn’t a full-time writer then. After retirement, I suddenly found a lot of time on my hands. Hence, time management became an issue. Initially, I was at a loss, resulting in a lot of wasted time. Gradually, I decided to follow my office routine, that is, get down to working in the morning at around 9-10 am and break at lunchtime, usually around 2 pm. This 4-5 hours in the morning resulted in solid, meaningful work. I wrote frequently for magazines, portals and also wrote books, including the one on the Indian freedom fighter, Jatindranath Mukherjee, popularly known as Bagha Jatin.

Frontlist: Your book ‘Bagha Jatin’ is rich in historical details. Can you describe your research process for this book? How did you ensure the accuracy and authenticity of the historical events and characters depicted in your narrative?

Somenath: Firstly, I collected a lot of books. These were of various types. I consulted four biographies of Bagha Jatin, particularly the one written by his grandson Prithwindra Mukherjee which is rich in details and also accurate. Next, I read the memoirs of several revolutionaries of those times. These not only provided me with many anecdotes on Bagha Jatin’s life but I also became acquainted with the nature of anti-British movements, particularly the militant movement in Bengal and elsewhere. Another type was the history books, how life was in colonial India, particularly Bengal, after the first war of independence in 1857: the drainage of wealth, the many militant organizations that were formed to oppose the British, the partition of Bengal, Swadeshi movement which triggered the first wave of struggles against foreign rule. It was also important to understand the militant movement from the British viewpoint, so I consulted some articles by their administrators. Last but not least was the literature of those times, particularly ANANDAMATH by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. It helped me to understand the spirit that guided the revolutionaries.

To check the data gleaned from the above sources, I got in touch with another grandson of Bagha Jatin, Sri Soumendranath Mukherjee, who lives in Kolkata. Apart from validating many historical details, he also gave me valuable family anecdotes.

Frontlist: Were there any particular anecdotes or stories about Jatin that you found particularly compelling?

Somenath: Obviously, it is the incident that earned him the sobriquet Bagha Jatin. It happened in 1906 when he was in his village Koya. Local people came to him and complained that a tiger was taking away their livestock. Jatin ran to the spot with just a khukri, a type of knife. With sheer courage and strength, he took on the tiger and, after a titanic struggle, was able to kill the beast. He was severely injured in the skirmish, and many thought he would not survive, or at least his legs would be amputated. But a reputed Doctor of Kolkata (then Calcutta) operated on him, and he was on his feet within two months. This is the single most amazing incident of his life. This made him stand out even in the midst of most hardcore revolutionaries. The British were also afraid of his courage and physical strength.

Frontlist: How do you think Jatin’s vision of armed revolution and his efforts to unify various leaders influenced the Indian freedom struggle?

Somenath: During the anti-colonial movement, particularly in Bengal and Maharashtra, many militant groups were formed. The two most important in Bengal were the Anushilan Samity and Jugantar. Jatin did not align himself with any of these organisations. This enhanced his stature in three ways. Firstly, he was able to remain free of the squabbles that plagued these entities; secondly, the very fact that he remained an ‘individual’ made him neutral, and all the revolutionaries, irrespective of their group, liked him and looked up to him for leadership and motivation. His role also contributed to reducing the factionalism between various groups. Thirdly it enabled him to chart his own path of revolution. His method of struggle had two important aspects --- acquiring arms from anywhere, even from foreign countries and particularly from the enemies of the British, and self-sacrifice, including martyrdom, which he believed would raise the Indian people from their slumber.

Though he was not aligned with any particular group, he collaborated with the great Rashbehari Bose in the attempted armed rising in 1915. He tried to import arms from Germany. Thus, he set an example, which was followed by none other than Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose when he allied with the Axis powers and invaded British India with the help of Japan. However the drawback was even though young men and women sacrificed in droves, it was not enough to motivate the masses. Thus Bagha Jatin’s last battle against the British failed to lead to a popular uprising.

Frontlist: ‘Bagha Jatin’ explores themes of nationalism, courage, and sacrifice. What message do you hope readers take away from Jatindranath Mukherjee’s story?

Somenath: The most important message that we can take from Bagha Jatin’s life is that young men must be imbued with a similar spirit of patriotism and nation-building. They must also be taught to create social awareness and harmony. For this, family and social upbringing are of utmost importance. Every mother should emulate the way Sharatshashi brought up her son. Though Jatin was initially timid, even at an early age his mother forced him to chase a barking dog or swim in a turbulent river without any help. This made him courageous and not averse to taking risks. He regularly did physical exercises which made him strong and powerful. It was due to this combination of strength and courage that he was not afraid to face British soldiers. His mother was also aware of making him strong spiritually, for which she read to him the writings of Michel Madhusudan Dutta, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya, and the Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata.

Frontlist: As Independence Day approaches, why do you believe it’s important to keep telling stories about India’s freedom struggles?

Somenath: Even today, after seventy-seven years of attaining freedom, many people say that India got independence the easy way, without any bloodshed or sacrifice, that it was given to us on a platter; some even say we literally begged for it. This is because we are accustomed to reading a very lop-sided view of the freedom struggle. We have come to believe that it is largely because of the non-violent movement that we achieved freedom. This is wrong. Our freedom struggle has many strands, each as important as the other. There is the militant movement, particularly in Bengal, Maharashtra, and Punjab, which started in the late nineteenth century. There are the Adivasi revolts, peasant and workers movements, and the historic efforts of men like Netaji Subhas Bose and Rashbehari Bose to free the country with foreign help. The fact is rivers of blood flowed throughout the country which ensured our freedom. We must know those men and women who laid down their lives. How many people know about Vasudev Balwant Phadke of Maharashtra, who built a ragtag army in 1879, when the Congress party had not even come into existence, and took on the might of the Imperial army? How many people know about Prafulla Chaki, who laid down his life trying to assassinate a British official, or Pritilata Waddedar, who laid the attack on the European club in Chattagram and led down her life, or Allah Baksh of Sind who opposed the formation of Pakistan and was assassinated allegedly by Muslim League goons. We must know about these unknown martyrs and so we must make it a habit of reading about their lives. Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Patel are undoubtedly great men, great freedom fighters but our knowledge of freedom fighters must not remain confined to them. We must educate ourselves about the entire gamut of our freedom struggle.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.